Chak

Chak

Background

The game of chess first arose from India (or so the common theory states), from where it evolved into western Chess in Persia where it spread to Europe and developed its modern form. East Asia has multiple rich forms of chess that offer something new but also infuse their culture into it. Many cultures throughout the world have a chess of their own. However, what about the native peoples of the Americas? Mesoamerica once had great empires. What if they had a chess of their own?

Chak is a game designed by Couch Tomato in 2021 specifically to answer this hypothetical question. The design philosophy was to start from scratch and use only the common elements from all forms of chess: a king, a rook-type piece, a knight-like piece, and some sort of pawns; the rest would develop organically infusing a specific Mesoamerican culture -- in this case, the Maya. For example, for the Maya and other Mesoamerican cultures, the native religion with ritual sacrifice was a fundamental part of society; the concept of an offering to the gods as well as the large temples are a key part of the game.

The name Chak itself is derived from the Mayan God Chaac, the rain deity who possesses war-like fury. This matches the setting of Chak, which is a battlefield along a river. Finally, two words of warfare in Mayan epics include “Chuc-ah” (capture) and “Ch’ak” (decapitation). In Chak, these are utilized as the win conditions of altar mate, and checkmate, respectively.

Introduction and General Rules

There are two sides, designated white and green, respectively. White moves first.

Board

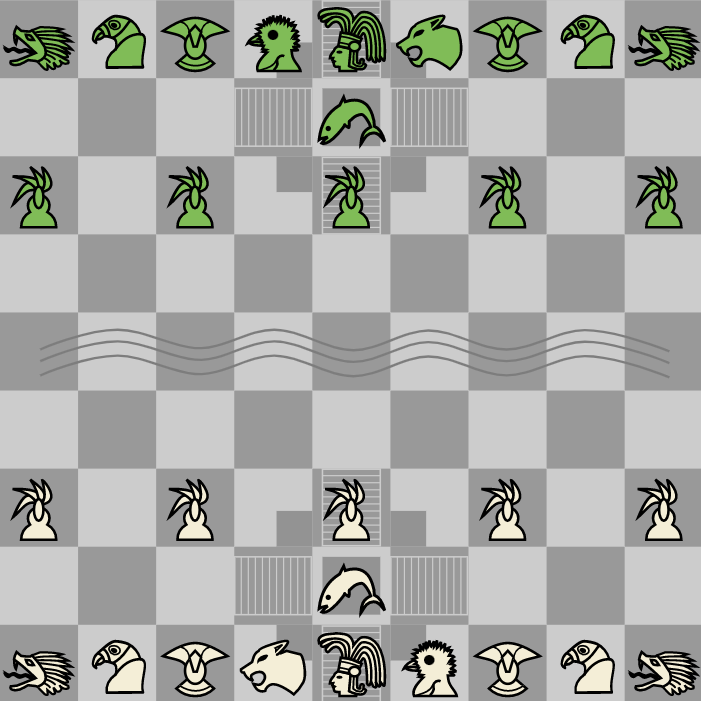

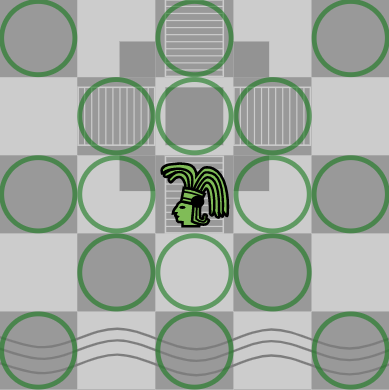

Chak is played on a 9x9 board as shown below:

There are three special regions:

-River, a special rank that marks the boundary for promotion. When certain pieces (the king and the pawn) move into the river, they promote. However, they cannot move back behind the river. Promoted pieces are committed to moving in the river and enemy side of the board for the rest of the game!

-Temple, a 3x3 region that has no special function. However, this symbolically represents the start of the king and contains the altar, which is described next. Strategically, the temple is important because many special tactics take place in this region.

-Altar, the central square of the temple. Moving your king into the enemy’s altar is one of the main methods of victory.

Goals of the Game

There are four ways to win:

Checkmate - Put the king in check with no legal moves.

Stalemate - A player with no legal moves loses (unlike in Chess, where it is a draw). This is considered a subset of checkmate in Chak.

Altar mate - Move your promoted king to the opponent’s altar without being in check to win.

Resignation - Your opponent resigns.

Other game-end conditions result in a draw:

Repetition - The same position is repeated three times.

50 moves - A draw can be claimed if no capture has been made in the last 50 moves.

Draw offering - A player offers a draw and the other player accepts.

Pieces

King (K)

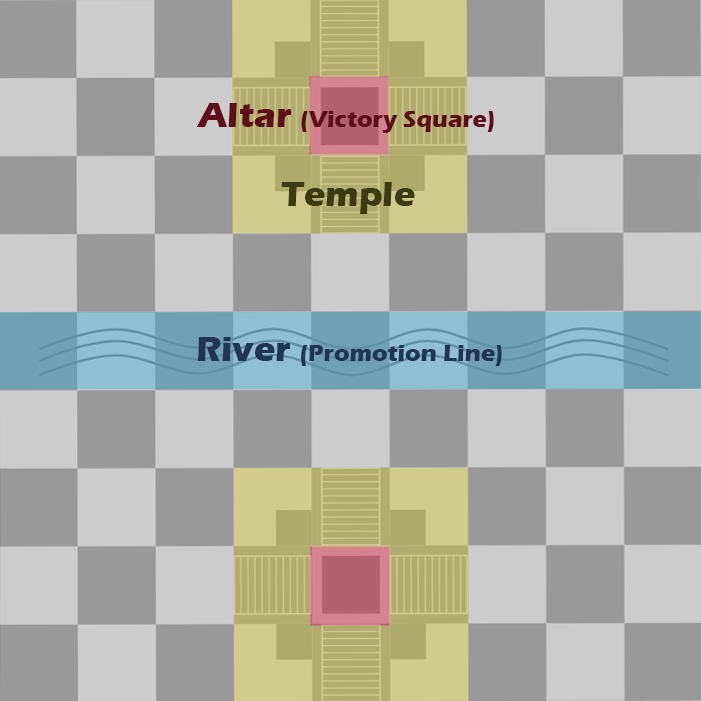

The King (Ajaw, which rhymes with Dachau) moves like a king in most classic forms of chess: one square in any direction. However, the king in Chak is unique in that it can promote upon reaching the river.

Divine King (D)

The Divine King moves up to two squares in any direction. It can also pass through squares that are threatened by the opponent’s pieces (in other words, it is not like the Western Chess king that cannot castle through check). Remember that as a promoted piece, it cannot go back beyond the river! The divine king has the ability to end the game by reaching the altar without moving into check. Because of its range, the divine king has the ability to deliver checkmate to an unpromoted king.

Note that the symbol used only differs slightly from the king’s. They are meant to be the same, but the slight difference is to help players see the promotion and also for the two forms of the king to be distinct on the board editor.

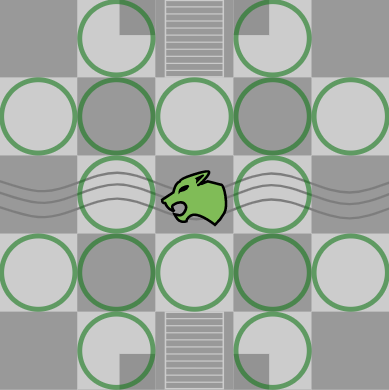

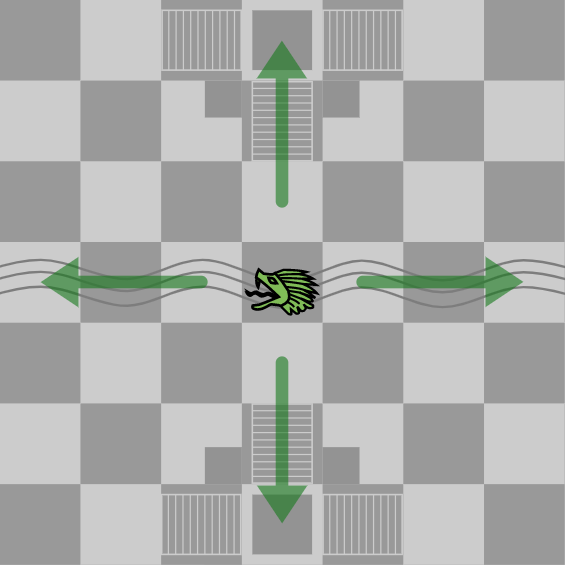

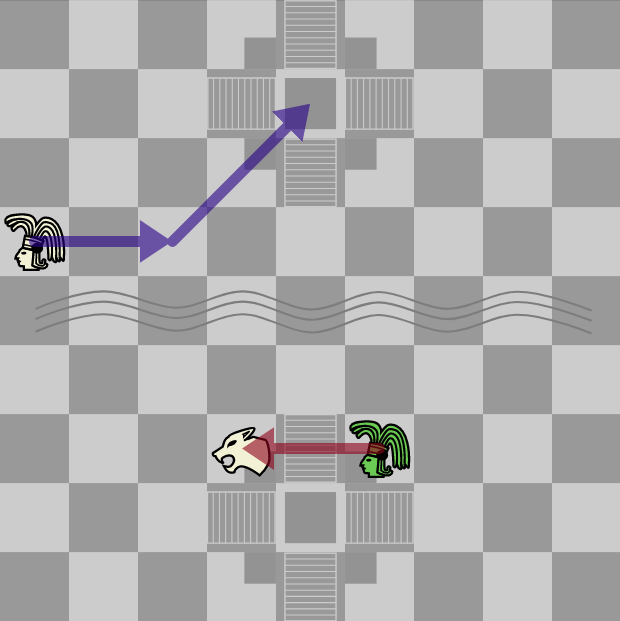

Jaguar (J)

The Jaguar moves like a hybrid knight and king: in detail, that is either 1) a leaping movement going two spaces in one direction and then one perpendicular to make an L shape, or 2) moving one step forward in any direction. This is generically also referred to as a “centaur” piece, and is the same as the General from Shogun Chess and Kheshig from Orda Chess.

The Jaguar is the most powerful piece in Chak, and its ability to fork multiple pieces make it incredibly dangerous.

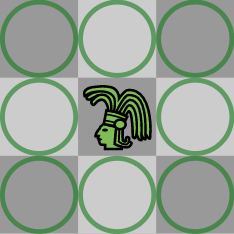

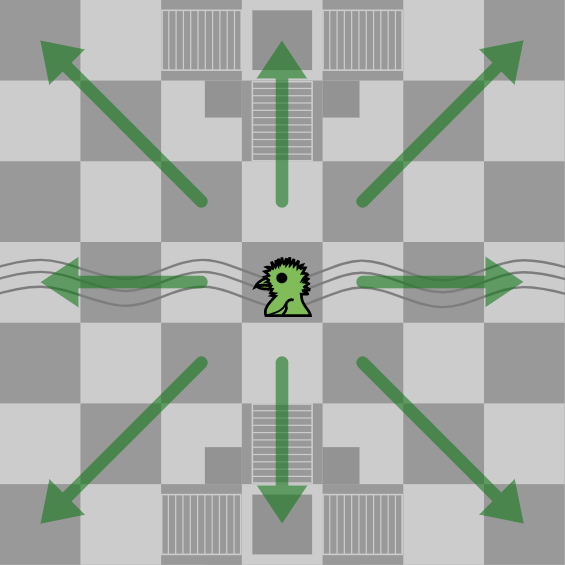

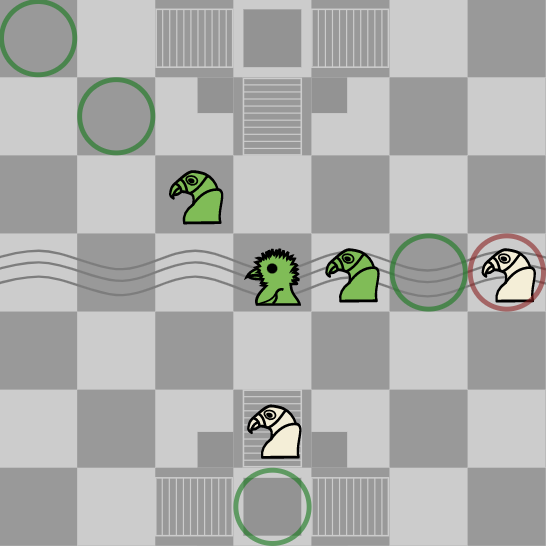

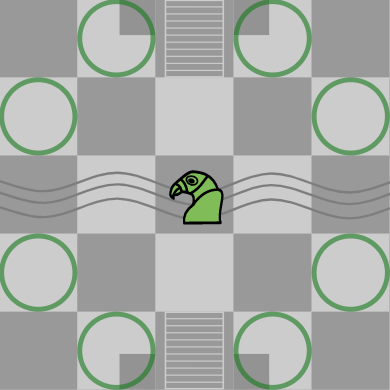

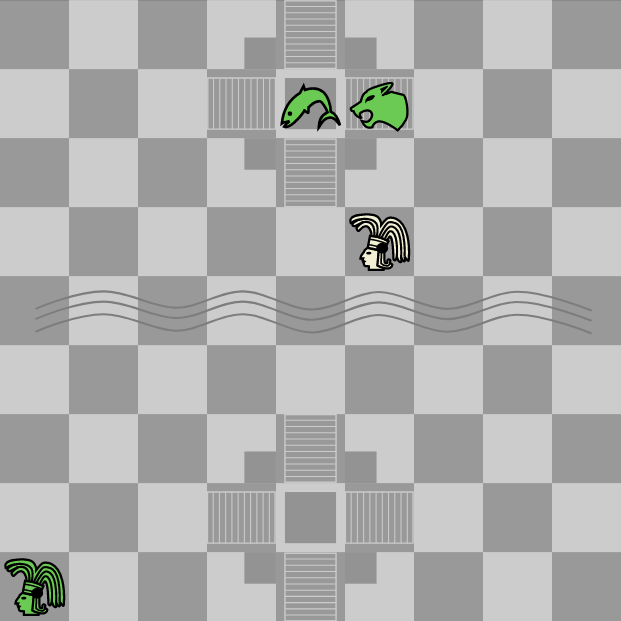

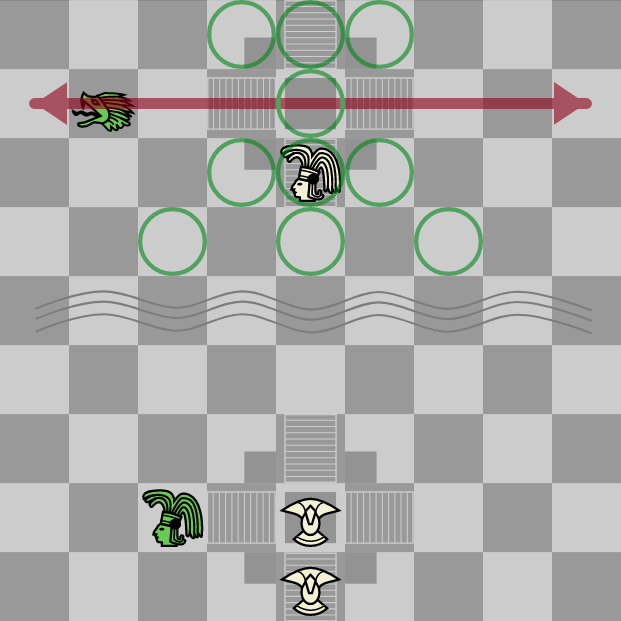

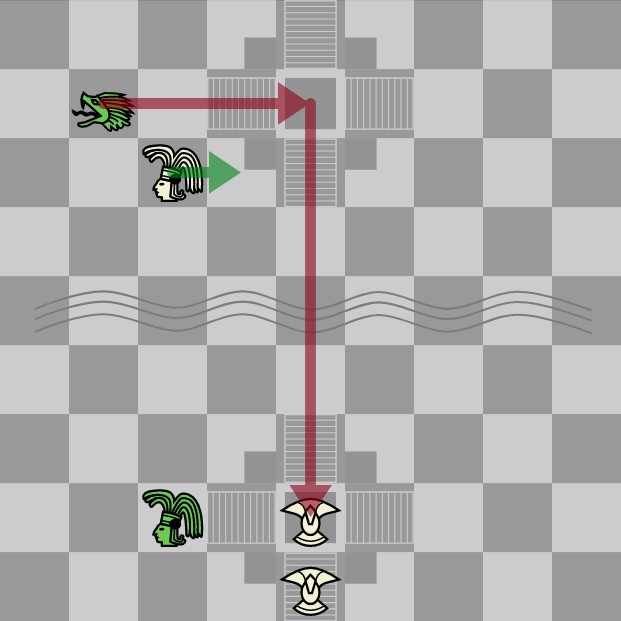

Quetzal (Q)

The Quetzal is a tricky piece; it is similar to the Chess queen in that it can move any number of squares in any direction (orthogonally or diagonally)… However, it needs to hop over an intervening piece first to do so. For those familiar with Janggi, this is similar to the cannon in that game, but with the addition of diagonal movement and without the restrictions of being unable to interact with another cannon.

The Quetzal is the second most powerful piece in Chak, but loses value significantly in the endgame.

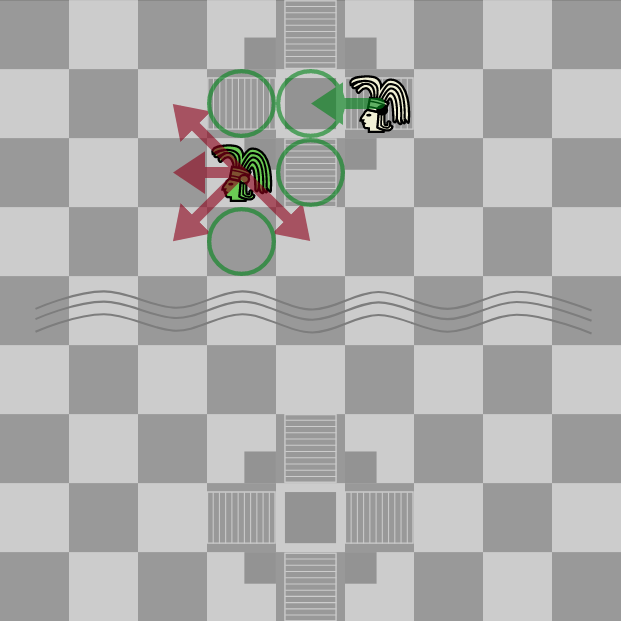

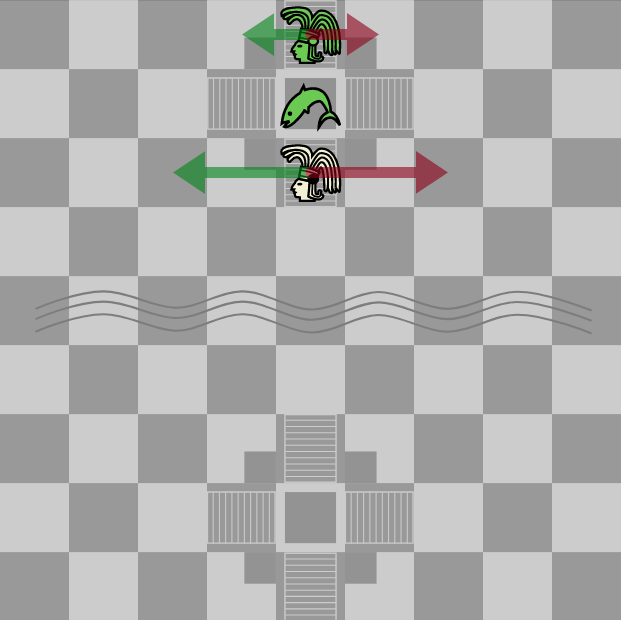

Example: In the following image, the quetzal can move the following spaces (red circle indicates capture).

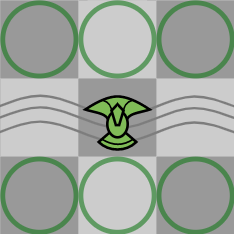

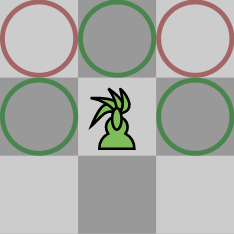

Shaman (S)

The Shaman moves one space diagonally or one space orthogonally forward or backwards.

The Shaman is one of the weakest pieces and is typically used more defensively due to its slow movement.

Note that the piece symbol is shaped to help remind you of its movement.

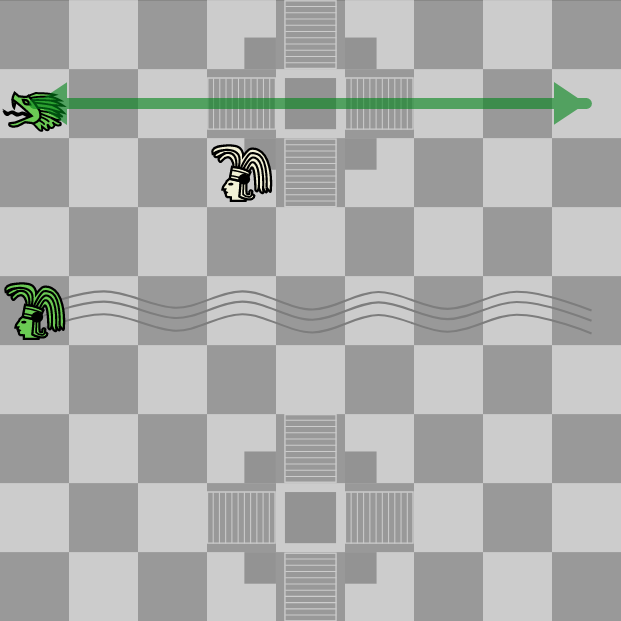

Vulture (V)

The Vulture is identical to the Chess Knight: a leaping movement going two spaces in one direction and then one perpendicular to make an L shape.

Serpent (R)

The Serpent is identical to the Chess Rook: orthogonal movement any number of spaces. This is the third strongest piece, after the Jaguar and Quetzal.

Pawn (P)

The Pawn can move either one square forward or one square sideways without capturing. To capture, it attacks one of the two forward diagonal squares. This is the same as a western Chess pawn but with the added ability to move sideways. Once the pawn reaches the river, it promotes into a promoted pawn, or Warrior.

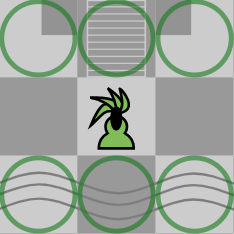

Warrior (W)

The Warrior (or Promoted Pawn) moves exactly like a shaman: one space diagonally or one space orthogonally forward or backwards. Unlike the shaman, it cannot move backwards across the river.

Note that the symbol used only differs slightly from the pawn’s. They are meant to be the same, but the slight difference is to help players see the promotion and also for the two types of pawns to be distinct on the board editor.

Offering (O)

The Offering does not move or capture; it blocks the altar until captured. The piece exists not only for thematic purposes (serving as the offering at each player’s own altar), but also serves as a mount for the quetzal. Finally, because of its position, it also helps prevent your altar from a lone divine king if your own king has not left the temple, potentially forcing a draw if all other pieces are off the board. Without the offering, the divine king would be able to displace the defending king and take the altar.

Piece valuation

Accurate piece values are unknown. However, the following piece ranking is generally accepted: Jaguar > Quetzal > Serpent > Vulture > Shaman > Warrior > Pawn.

Strategy - Pieces and Basics

Quetzal: One primary tip for beginners is always pay attention to the lines of sight for the quetzal. Specifically, at the beginning of the game, any piece that moves in front of the quetzal opens it up to an attack on the opposing jaguar, which is a slightly favorable move.

Jaguar: Regarding the jaguar, build defenses and prevent the jaguar from crossing the river. If the jaguar crosses before your pieces are coordinated, it can singlehandedly capture multiple pieces with ease.

Pawns: Pawns in Chak are actually quite flexible and strong and also threaten promotion very early. Because of all this, they are not as "expendable" as pawns in other games; make sure to get good value if you are wiling to trade off your pawns, as a one pawn difference at the end of the game could make the difference between a victory and loss.

Tempo is very, very important in Chak, as it ultimately boils down to a race to get your king to the other side. Positional play is also very important.

Strategy - Endgames

Endgames often boil down to getting the king to the Altar faster then our opponent. In this section we'll focus mostly on endgames where Divine King is the only attacking piece.

King vs King

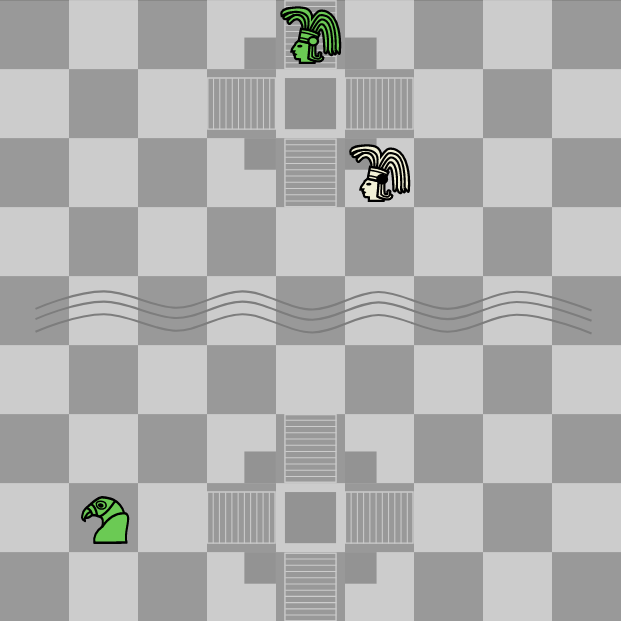

With the king being the only defender's piece, the win is pretty easy. The attacker only needs to reach a position with their king on the side of the altar and the defending king in the corner with the defender to move. Then, the defender is forced to move their king away from the temple, allowing the attacker to move their king to the altar.

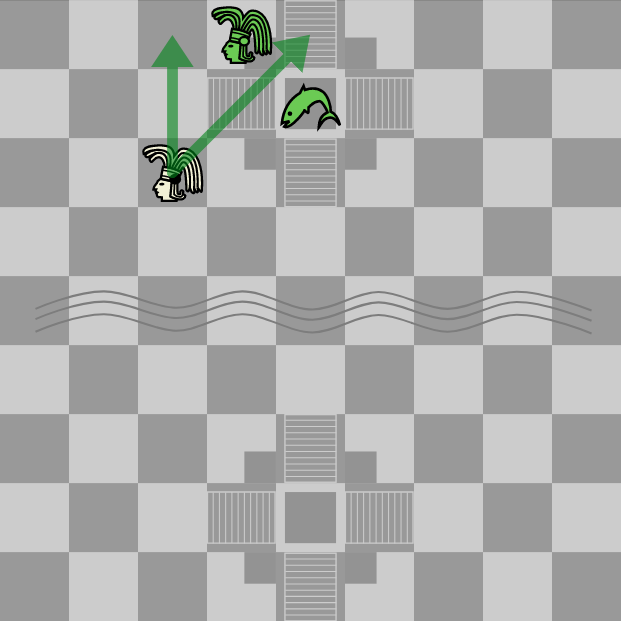

With the offering still there, the attacker can still win, but it's trickier. What the attacker should be aiming for is not altar mate, but rather this stalemate:

An example line on how to force this position goes like this

Dd6+

Kf7 Dd7+

Kf2 De8

Kf9 Df7+

Ke9 De7!

…and we've reached the following position:

where green is in zugzwang; moving the king to either side allows white to respond with a stalemate.

However. if the defender has one more piece (except for an immobile quetzal) things change dramatically. No matter if the offering is still there or not, there is no way for the divine king to check the defender's king and cut off all squares within the temple it could go in one move, so green can always either move their other piece, or move the king within the temple. The only thing to be concerned about is blundering the other piece, so it's recommended to keep it on the last 4 ranks as the divine king can never get there. Once it's there, the defender can just move (and safely premove) either the piece around the last 4 ranks or the king within the temple, and the attacker is left helpless.

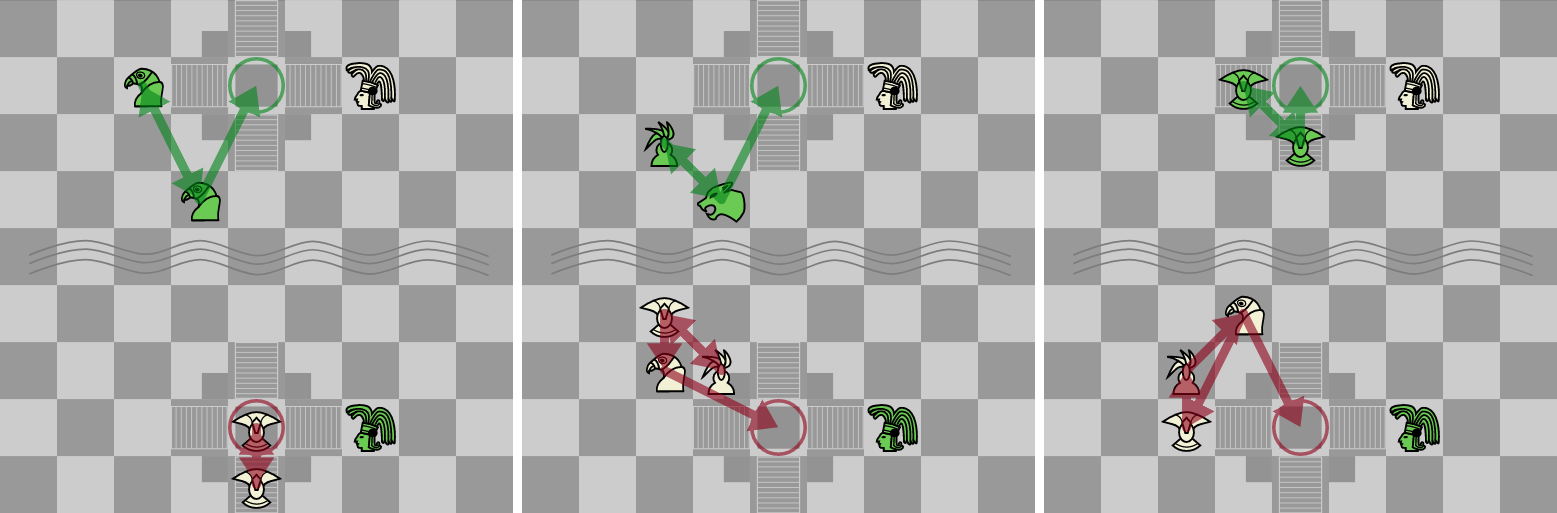

Fortresses

A fortress is set up with a piece defending the altar and every piece being defended. Against such a setup, a lone king is helpless.

All these examples are bareboned in a sense that if either side decided to move any of their pieces away from around the temple, they can no longer form a fortress. If both sides have a bareboned fortress like in the above diagrams, the game is a dead draw. On the other hand, if one side has a bareboned fortress and the other has a fortress plus any extra piece, as long as that extra piece can safely cross the river without being captured and join the attack on the fortress, it's almost always a win for the side with the extra piece.

Other defenses

Jaguar

In a lone Jaguar vs a Divine King endgame, either side can force a draw by repetition…

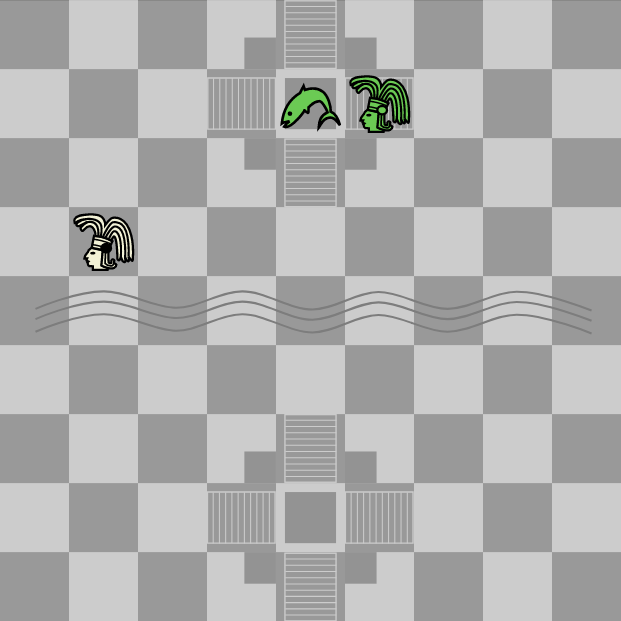

…except when the side with the Jaguar can just ignore their Jaguar being under attack and run their King towards the altar like in this position.

White wins by just moving their King to c4 or c2 and to the altar on the next move.

With the Offering still alive, it's a different story.

In this position, green can go 1. Jf9; white's only move to keep attacking the Jaguar is Df7, but after 2. Je9+ Dg then 3. Jd9, then there is no way to attack the Jaguar in one move, and if white spends 2 moves to do so, green has one tempo to do something meaningful on the other side of the board. If white gets their King to f9, then after Jd8, there is again no way to attack in one move, so it's better to get the King to d7 so again we can force the Jaguar to move twice. If the draw by 50 move rule is close it might be important to remember those exact lines to enforce wasting as many moves as possible as green or save as many as white.

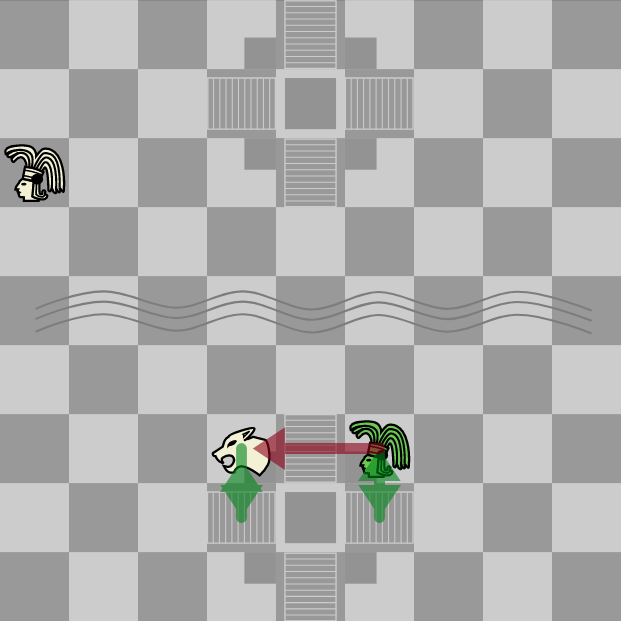

Serpent

The Serpent as a long range piece can easily move back and forth along the second rank, keeping an eye on the altar. If the Divine King stays on squares from which it can reach the altar directly, the Serpent has to stay there and is usually useless in breaking through the enemy fortress. So if green has a fortress as well, it's usually a draw.

However, moving away from the highlighted squares to harass the Serpent can be costly, like in this position:

White has abandoned the altar, allowing green to go Re8 and skewering both Shamans. If white moves the King back, e.g. to d7, green takes on e2, and as the Serpent still defends the altar, green is winning. If white tries something different, green can take one of the Shamans and still win.